Ascesis

The term “ Ascesis” comes from the Greek (askêsis) and originally means exercise or training. In ancient times, this term was used to refer to the activities of athletes, and the philosophical adherents of Stoicism (Stoics) applied it to moral self-improvement. So, ascesis is some form of activity which aims, through austere activities, to perfect the adept in his chosen discipline. The key words in this definition are “austere activities” because the practice of ascesis really involves not just a training, occupation, or stance in life, but extremely austere measures of influence. Overcoming oneself, overpowering oneself, and striving for the goal through any obstacles is the life credo of true ascetics.

This position is often based on the dualistic idea that the body and spirit, although closely connected, are not one and that in order to elevate one’s spirit or consciousness, it is necessary to free oneself from the fetters of the bodily. The body chains the consciousness to its physiology, its animal foundation, and therefore grounds it, alienating it from the higher (divine) perception of reality. According to this concept, it is implied that by means of various kinds of restrictions, abstinence and ignoring the needs peculiar to the human body, one can increase the control of consciousness over its material essence, reversing, so to speak, the sphere of influence.

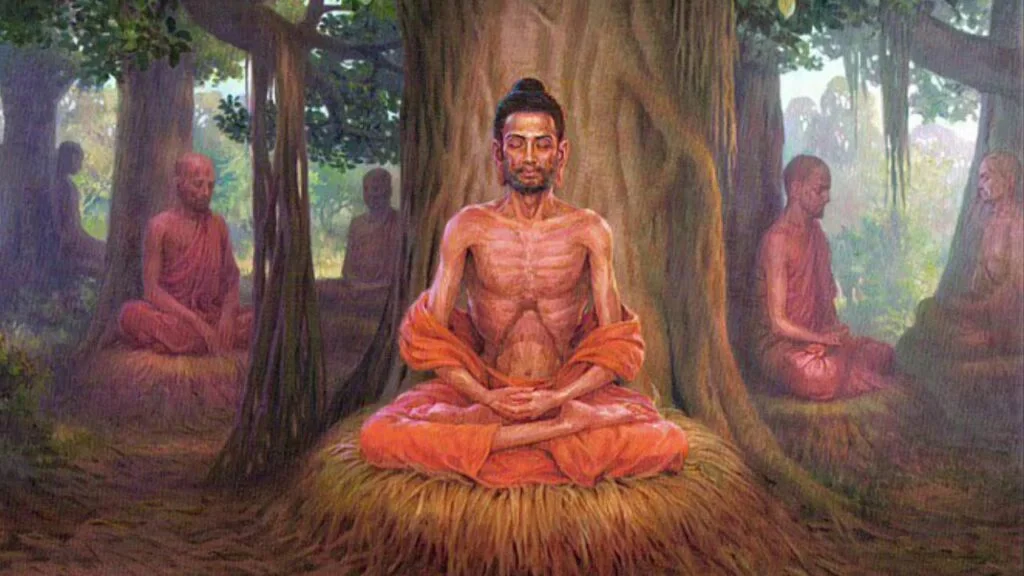

The picture is of a real ascetic that my yoga tour group and I met in one of the caves in the Himalayas. He and his Dharma friend have been practicing here for 11 years. According to the legend, this is the cave where the Pandava brothers (heroes of Mahabharata) stayed for some time when they left the society. Photo by Valentina Ulyankina. Near the mountain village of Gomukh. 2017.

So, at the level of the body, ascesis usually looks like: altruistic physical work (including spiritual practice), measured nutrition (both in quantity and quality), non-violence and a vow of celibacy. Perhaps for everyone the limits of discomfort in this matter will be different, but there are also outright transcendence of human possibilities. One such striking example is the extremely rigorous practice of Siddhardha Gautama, the enlightened ascetic who was later named Shakyamuni Buddha. In his tireless search for an answer to the fundamental questions that had interested him for some time, namely, how to help society rid itself of suffering, he probably surpassed all his fellows on the spiritual path. Here is how he himself describes his experience:

“When a single berry alone was my food, my body became extremely thin. My limbs became thin as a result of such scanty nourishment; like a braided plait my spine was bulging as a result of such scanty nourishment; as in a ruined house the rafters are broken and sticking out in different directions, so my ribs were sticking out in different directions as a result of such scanty nourishment; as in a deep well the surface of the water seems deeply buried, so my pupils, sitting deep in the eye sockets, seemed deeply buried as a result of such scanty nourishment. And just as a bitter gourd cut raw shrinks and shrivels from the wind and sun, so the skin on my head was shrunken and shriveled as a result of such meager nourishment. And if I wanted to touch the skin on my stomach, I touched my spine; and if I wanted to touch my spine, I touched the skin on my stomach as a result of such scanty nourishment” (Uhlig G. ‘The Buddha, His Life and Teachings’). “People who saw me said, ‘Hermit Gotama is black.’ Others said, “Hermit Gotama is not black, but brown.” Still others said, “Hermit Gotama is neither black nor brown, but has golden skin.” The pure and bright color of my skin was so badly spoiled, simply because I ate so little” (Maha-sacchaka sutta).

The hermit Gautama spent about six years in such deprivations, after which, having practically lost his life, he came to the conclusion that he would not attain enlightenment by means of this path: “But by leading such a way of life, undergoing such changes, mortifying my body, I have not attained the highest state attainable by man, the full acquisition of blessed knowledge, and why not? Because I have not acquired that blessed knowledge which, if you have mastered it, guides and leads you to the complete cessation of suffering” (Maha-sacchaka sutta).

Eventually Siddhartha recognized that in order to achieve spiritual goals one must adhere to the “Golden Mean,” that is, on the one hand, not to expose one’s body to mortal danger in one’s practice, and on the other hand, not to sink into the swamp of worldly pleasures.

However, how can we keep to the golden mean when, living a social life, we are constantly involved in various kinds of situations that are full of provocations, temptations and passions? Perhaps this is why the following two levels of ascesis were invented – the ascesis of speech and the ascesis of mind.

At the level of speech, it is assumed that the practitioner renounces: swearing, profanity, gossip, discussion, lying, insults, arguing and other such destructive actions. By doing so, he at least cuts off the possibility of getting into questionable situations that would provoke him to harmful actions. As a result, he saves more energy, which he has the opportunity to channel into reaching new spiritual heights, if only for the sake of his own evolution. However, despite the fact that in theory it looks quite logical and correct, having tried to apply such an asceticism in practice, we quickly become convinced that it is not possible to last very long in this way. Why does this happen? Because our speech is an arbitrary action from the work of our mind. That is, the mind actually determines how we react to various situations and what we end up saying. The mind is the cause and speech is the result. Accordingly, in order for our speech to be adequate, it is necessary to work first of all with the mind.

Here we come to the third form of asceticism – the asceticism of the mind. At this level, a more subtle work takes place: the practitioner tries to turn his attention from outside to inside in order to better understand the mechanisms of consciousness. He tries to take control of his feelings and emotions, to work through the negative traits of his character (pride, envy, greed, etc.).

So the question arises, which form of ascesis would be more appropriate to practice: body, speech, or mind? In fact, there is no right and wrong answer here. Everything depends on the level of evolution of each individual person, his karmic experience, which can be traced far not only in this life. It will be actual for someone to reach his mind through his body – cutting off the influence of animal nature, liberating the consciousness from the fetters of the body. Another person will find it more accessible to watch his speech and there are many reasons for this (perhaps this person has no time and opportunity to deal with the body at all). A third will have access to mindfulness techniques. And someone will do all three of these approaches at the same time, skillfully combining them with each other. There is no universal way, but fortunately, there are specific tools that will help us focally achieve this or that intermediate goal. But how and in what sequence to apply these tools will be suggested to you either by an experienced teacher, or by your good karma, perhaps by intuition, or by infinitely compassionate higher forces.

In this article, I offer one form of bodily ascesis, which can be considered preparatory to more serious practices. I first learned about it once from Andrei Verba. Despite the condescending term “preparatory”, this technique undoubtedly has an immediate impact and tangible effect on both our body, energy and mind. That is, it is an extremely effective technique, the application of which will help you to make significant progress on the path of self-development.

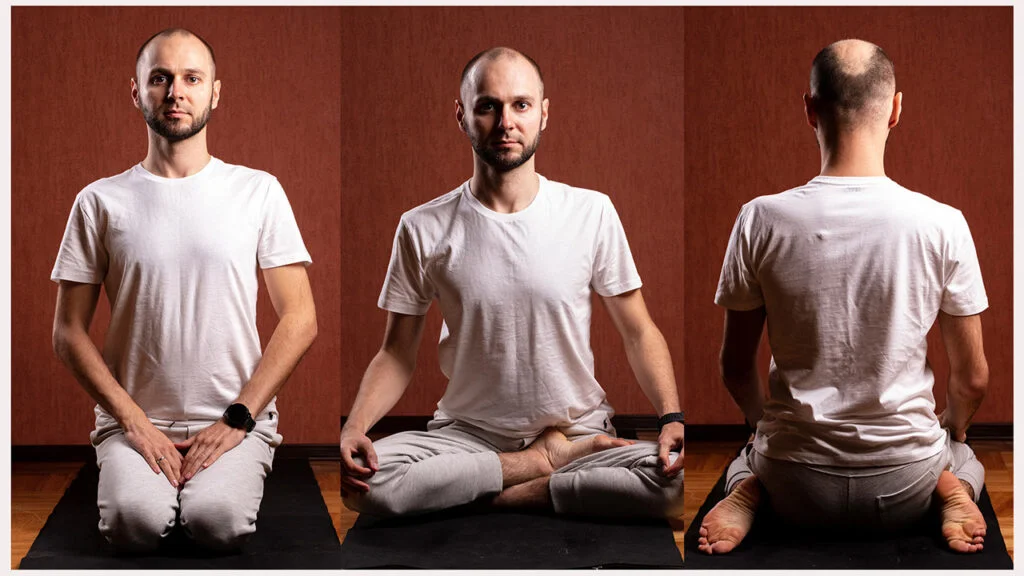

So, the essence of this action is to hold the meditative positions of the body (Padmasana, Ardha Padmasana, Virasana, Vajrasana and other similar asanas) for a long time. It is done [technically] very simply – you need to take one of the above positions and hold it as long as it is available to you now, according to a timer. As time goes by, the stay in these asanas should increase until you reach at least one hour. In the case of asanas that are asymmetrical (like Half Lotus), the exercise should be performed on each side for the same amount of time. Each of these asanas has some contraindications, please study them yourself before you start your practice.

This technique will help you:

- more effectively open the hip joints and ankles (compared to classical Hatha yoga complexes, where asana is held for 1.5-2 minutes, here your influence on the connective tissue is much longer, and therefore more effective);

- to prepare the body (legs and back) for long meditative practices (i.e. to develop the skill of keeping the body in a static position for a sufficiently long time);

- to turn the flow of energy from the lower centers to the upper centers, which automatically elevates consciousness (in these asanas you block the flow of energy downwards, which naturally turns it upwards);

- cultivate tolerance and humility (voluntary prolonged discomfort literally rewrites destructive patterns of resentment and dissatisfaction with life);

- calm the mind and increase its concentration (at the very least, by anchoring it to your own discomfort – which is really the here-and-now state).

In addition, there is an authoritative opinion that such practice of asceticism helps to transform (burn) conditionally negative karma (i.e. negative consequences of past actions) and to accumulate precious energy of tapas (energy which on the subtle plane serves as a “money” for getting what one wants). These two points I have deliberately separated from the rest, because on the spiritual path they are perceived by adequate practitioners mainly as a consequence, but not as the very goal of asceticism. In history there are a great number of cases when due to their own ignorance, selfishness and pride, asceticism, unfortunately, practiced just to achieve material gain, but not spiritual growth. One of the clearest examples is a demon named Hiranyakashipu.

According to the Vishnu Puranas, this demon, in order to attain immortality, indulged in unrestrained asceticism, immersing himself in meditation at the foot of Mount Mandara. Since immortality itself cannot be obtained by anyone in this material world, he formulated his intention as follows: “I want to become invincible, so that neither sickness nor old age will approach, and so that I will always be protected from any enemies.” Hiranyakashipu’s ascesis was that he stood naked in a huge anthill and stayed there in meditation for an incredible [by human standards] number of years (apparently by nature he was not quite human, that is, not as we imagine). During his asceticism, worms, ants and other insects almost completely ate his body – he retained his vital air (prana) only in his bones. Eventually he achieved his goal and received the desired blessings from God Brahma, after which he brought much misery and oppression to the world. However, as is always the case in such situations, an agonizing death and an unbelievable amount of negative karma overtook him. It is difficult to imagine where and in what conditions he had to reincarnate after what he had done.

This and many other stories show us colorfully every time that we don’t need to trade our spiritual practice for false values – it never ends well. But our lives are full of temptations, full of desires and full of passions. It is not easy to keep ourselves within the bounds of true values – light and altruistic values, but apparently that is the way it was meant to be. Everyone will have to go through his own lessons and also have his own [in their karmic gravity] consequences from them.

Sources used:

Specialized articles and video materials on oum.ru website

Responses